Iratus is the demon charged with punishing those who have harmed children. As more souls come to his ring of Hell, Iratus wonders about his effectiveness and goes “Topside” to take the punishment to the innocence-takers, before they can take more innocence. While on Earth, Iratus frees sixteen-year-old Raven Mijares from human-traffickers. The two form a bond, and Raven teaches Iratus what it means to be human while helping him uncover the true reason he was tricked into coming to Earth.

ring of Hell, Iratus wonders about his effectiveness and goes “Topside” to take the punishment to the innocence-takers, before they can take more innocence. While on Earth, Iratus frees sixteen-year-old Raven Mijares from human-traffickers. The two form a bond, and Raven teaches Iratus what it means to be human while helping him uncover the true reason he was tricked into coming to Earth.

Chapter One

The Old Stone Church

The Stone Church has many mysteries surrounding it—including several about the Stone family (the caretakers who have watched over it for over a hundred years), but maybe these mysteries aren’t all merely the result of coincidence and bad luck. There may be an entity of true evil residing in the church.

The Stone Church has many mysteries surrounding it—including several about the Stone family (the caretakers who have watched over it for over a hundred years), but maybe these mysteries aren’t all merely the result of coincidence and bad luck. There may be an entity of true evil residing in the church.

A Very Unfriendly Vice: Part 1— Inside In

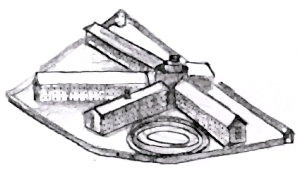

Just north of the geographic center of Mystic Island, is Springback Prison. There aren’t many inmates in the prison anymore. Most of the facility’s wings are now vacant. The only people incarcerated there are pretty much those that committed crimes on the island, or those temporarily locked up in the wing of the prison now used as the island’s police station. The prison, opened in 1913, was an anomaly to most. No one quite understood where the name came from, or why a prison was built on an island which was essentially envisioned as a summer vacation destination. Most figured it was because the prison would be less prone to break-outs, being that the only ways off the island were by boat or by bridge. Unfortunately, in 1918, three convicts did break out, causing a havoc few want to admit ever occurred. But this story isn’t about those three men (all of whom at their individual trials, swore a mysterious figure in the The Old Stone Church had precipitated each of their crimes which landed them at Springback). This story is about Cornell Philips. Cornell’s story is one of those tales that tightrope lucidity and madness. Cornell might tell you it was actually an over-lucidity that had hastened his crime. Now it is always quiet at night. And that’s all he ever wanted. He has a lot of time to reflect on things. In fact, more time than he needs, really. He—maybe I’ll just let Cornell tell his own story. Like most people locked away in a prison, and although they never admit to it, Cornell is always eager to talk to someone. Especially anyone who will listen:

Just north of the geographic center of Mystic Island, is Springback Prison. There aren’t many inmates in the prison anymore. Most of the facility’s wings are now vacant. The only people incarcerated there are pretty much those that committed crimes on the island, or those temporarily locked up in the wing of the prison now used as the island’s police station. The prison, opened in 1913, was an anomaly to most. No one quite understood where the name came from, or why a prison was built on an island which was essentially envisioned as a summer vacation destination. Most figured it was because the prison would be less prone to break-outs, being that the only ways off the island were by boat or by bridge. Unfortunately, in 1918, three convicts did break out, causing a havoc few want to admit ever occurred. But this story isn’t about those three men (all of whom at their individual trials, swore a mysterious figure in the The Old Stone Church had precipitated each of their crimes which landed them at Springback). This story is about Cornell Philips. Cornell’s story is one of those tales that tightrope lucidity and madness. Cornell might tell you it was actually an over-lucidity that had hastened his crime. Now it is always quiet at night. And that’s all he ever wanted. He has a lot of time to reflect on things. In fact, more time than he needs, really. He—maybe I’ll just let Cornell tell his own story. Like most people locked away in a prison, and although they never admit to it, Cornell is always eager to talk to someone. Especially anyone who will listen:

When I lay down and the sheet is still cool, I consider getting some shut-eye. But that rarely works out and the sheet warms up around my legs and torso—before you know it, I’m kicking it off and laying there, my eyes tracing the slatted shapes cast into my cell from the cold corridor. Nighttime sounds have a mysterious quality here and each imprints its own stamp into the thin silence. Most times the sources of these sounds are indecipherable— retches of vomit, the crest and release of distant snores, the punctuation of a head bouncing against concrete during some conflict—yet, I am grateful for the buffer of bars between us.

I learned to savor nighttime quiet at a young age; in our family it never came without resistance. The only times I had a chance at peace were the nights at Half Moon Pond, and even then I needed to wait out my mom’s monologues about the crappy hand life had dealt her, or my little brother, Jesse, whining that he wasn’t tired and hated sleeping in a tent. It didn’t take me long to learn that the dark line inside mom’s screw top wine bottle was the sand of an hourglass and as soon as it was drained she’d be off to the tent with him, and I’d advance a step toward peace. While Half Moon was certainly not Club Med, I cherished those nights. We didn’t get many vacations when I was a kid and if mom took us camping, I knew that that was about as good as it was going to get. Like anything else my family did, these trips were threaded together by a fragile budget and mom’s vacillating whims.

The first time we ever camped at Half Moon, it was a fragile time for our family. Even though I was only eight, I knew when dad left us it was going to weave complexity into our lives. I didn’t doubt his love for me and Jesse —hell, he probably even still loved mom—it was himself that he came to despise. And a small piece of eight-year-old me felt guilty, watching out my window through a scrim of fog, when he finally drove away. It followed one of their fights, the words muffled by my bedroom door, a toxic finality sealed when he walked out. I knew mom intended for the camping trip to heal us as a family—a newly forged unit of three. And in a lot of ways it served that healing purpose, but it also sort of excised me from childhood and left me longing to touch something forever beyond my reach.

When we arrived at Half Moon, I didn’t know what to expect. My imagined camping experience consisted of neatly erected tents, marshmallows, and spooky stories by the fire. I figured mom would take care of the work—cooking over the fire, tidying the ground near our tent, tending to Jesse—and I’d be free to roam the edge of the pond to trap frogs beneath my palms or venture off into the woods to test my fear of snakes. Reality hit hard once we started searching for our site and she started peppering me with chores. A thin strip of dirt road bisected the campground and she drove way too cautiously and charged me with finding a good site on the pond side. Our car crawled along at a speed I’d expect if we were looking for a lost earring in tall grass. A sheen of sweat blossomed on her forehead and I wondered why it was so important for her to find a site near the pond. The vacant wooded sites we passed looked perfectly fine from my perspective. She explained that you needed to arrive early in the day to score one of the pond sites and that we may have missed our chance. I looked out at the water where a cluster of pale bodies splashed around or floated on chintzy rafts beneath the noontime sun, and I thought that the wooded sites might actually be more attractive since we wouldn’t have to listen to them out there horsing around. But just as I made that assessment, she chirped excitedly and pounded the steering wheel with her fist. Our car nosed into the empty pond side site and we all tumbled out, Jesse already starting to whimper his complaints from the car seat.

Before we even unloaded the gear from the car, I looked out at the pond and was glad we’d persevered for that site. A small row boat, roped to a nearby buoy, bobbed an invitation to me from the water’s surface. I didn’t know if someone had left it there and would be back to retrieve it or if it actually came with the site. I knew better, though, than to show any interest in front of mom. Even if I had a life jacket, there was no way she’d let me go on the boat by myself and she also wouldn’t trust herself with a two year old out on the water. Jesse would anchor her to the shore for the duration of our camping trip. So I bookmarked the row boat in my mind and went to unload the car.

I suppose as an adult, I could’ve lived with the sounds of what the police later called “just plain life noises”—a patter of Mr. Morris’s footsteps through the ceiling above my living room or the occasional barks from downstairs when Hilda’s mutt took exception to the postman on the front porch. But the disturbances weren’t so benign. And that’s why I considered measures to make them all go away.

I took a cordial approach as the noise problem surfaced on my first day in the apartment house. My tolerance for distraction was pretty robust when I’d moved from my mother’s house into the new pad, and I wasn’t quick to let a yipping dog or a heavy-footed old man morph me into a pissy neighbor. After all, a noisy apartment seemed a more attractive option than staying with mom any longer. I spent that first day lumping consignment shop furniture from a rented van up to my place on the second floor, and with every trip I was forced past that asshole dog yip-yip-yipping, sputtering in circles on its chain in the yard. By sundown, I couldn’t be bothered with the dog, now yip-yip-yipping in the apartment below me; I was bone tired and flopped out on the futon with a bottle of Molson. But by the time I was ready to surrender to sleep, it was clear that the mutt had plenty more stamina.

The muscles in my legs protested as I eased down a flight to the apartment on the first floor, and from out there in the hallway I listened to the barks intensify until I decided there was no way anyone could be home. I actually felt a fleeting notion of pity as I ceremoniously knocked on the door and readied to climb back up the stairs. But the door opened and a heavy odor fell into the small landing where I stood—the kind that might seep from a long forgotten box in an attic. Hilda stood there in her floral-print house dress. Dust rose like confetti in the lamp-lit room behind her and she grimaced at me as if I were the annoying one. My first inclination was to introduce myself as her new neighbor and promptly retreat back up the stairs without mentioning the dog. But when the mutt approached the open doorway and snarled at me, I couldn’t let it go. After a brief moment of contemplation, she scowled and agreed to “keep a lid on the little dear.”

I walked back up to my apartment and sat on the futon just as the pounding began upstairs. At first, I wondered if maybe someone was hammering, but more like a sounding weight moving across the floor, and later that night I met Mr. Morris for the first time. He was much nicer that Hilda, but that didn’t make the continued pounding any more palatable when I stretched out on the futon with pillows pressed against the sides of my head. I was exhausted. Sleep, however, was not nearby. On that first night, I quickly realized that I was sandwiched by noise. When the dog barked below me, it was as if up above me Morris started dancing to that canine’s song. My new floor and ceiling had become a very unfriendly vice pressing away any chance of a quality night’s sleep.

Some nights I feel badly about everything that happened—particularly with Morris upstairs. That old bastard just gnawed on my last nerve. Part of the problem was the shoddy construction of a cardboard-thin ceiling that amplified every step he took. I could envision his bathroom habits, as momentary rhythms of gushing water let me know he was shaving and the lengthy humming of pipes signaled a shower. He may have been a man, but his bladder seemed systematically programmed to fill up twice every night. 11:55 and 2:15. It wasn’t fair that he was the one who had to take a leak and I was the one who suffered the resulting insomnia. I tried not to let it bother me and just get back to sleep, but it was always at least an hour before I fought off the annoyance. When he started dropping things—shoes? books? goddamn bowling balls from the sound of it—that’s when I really felt nudged to the edge of noise tolerance. And even though I planned everything with precision, I still have a tough time accepting any responsibility for eliminating the sounds of Mr. Morris.

You would’ve done the same thing if you were me.

And then there was Hilda downstairs. If it wasn’t her vacuum cleaner or her goddamn hairdryer, that mangy half-breed beagle was enough to drive anybody with a set of ears over the edge. Not that I ever exactly went over the edge—by my estimation, anyway. It was just that I sat there like a eunuch in a whorehouse one too many nights, unable to do anything but plug fingers in my ears, my mind blazing with possibilities for fixing the problem.

I started to focus on Mr. Morris because that was where my sympathy pooled. If I could somehow muster the balls to take care of him, then the dog would be cake. See, Mr. Morris only had one leg, which you’d think might make him a fine neighbor as far as the noise is concerned. I could rest assured he wasn’t going to be up bouncing around to some Jane Fonda video or any happy horse shit like that at the crack of dawn. He got the leg blown off by a land mine back while he was in the service and it was actually a pleasure listening to him tell the tale wrapped so neatly in war hero luster. I felt bad for him when he told me how the VA screwed him out of insurance benefits for so many years. And, it was a feel-good moment when they offered assistance with a prosthetic limb.

I was headed toward the bus shelter across the street that day to wait for the Downtown Express when Mr. Morris stepped off the idling #39 bus. His mouth curled into a bashful grin when he saw me, like a kid on Christmas morning hoarding a secret knowledge of Santa. I made a half-witted crack about him looking like he just got lucky with some supermodel and he hoisted the paperwork from the VA like a trophy and told me his news was much better than that. Beauty fades, he said, but titanium is permanent. It turned out that the limb they equipped him with must’ve come from Walmart because the rubber nub at the end of that titanium ankle wore down after exactly two weeks. Morris insisted he liked the feel of it better that way. I wanted to shoot down to the local VA office and recommend a head exam for Mr. Morris. From that day forward, every movement above the ceiling in my apartment sounded like a lethargic SOS message.

Whenever I voiced my complaints about the noise to any one of my somewhat reasonable acquaintances, I was given well-intended advice. Just go up there and ask the old guy to tread more lightly on your ceiling. Call the cops. Put a pillow over your head and just try to get some sleep. At one time or another, I tried all of those things and nothing proved to be anything other than a very temporary fix. One night, I came home from The Dutch Horse Pub after watching the Celtics squander an overtime lead and I could hear his hollow thuds up there before my key even passed into the lock. It sounded like a blind mannequin, gifted with life, was making a frantic attempt to get out of his apartment. I continued up the next flight of stairs, my balance wobbled by the sympathy whiskey doled out after the basketball game, and pounded on the door. It took him a minute to get there and the look on his face spelled genuine surprise. I lied that I needed to get up for work in the morning and that I couldn’t fall asleep with the racket of his footfalls overhead. Later, it dawned on me that I was still wearing my parka during the conversation and I wondered if he’d noticed. Mr. Morris nodded a brief apology but resumed his heavy-footed approach to life after a five minute respite.

By that point, I’d been living in the apartment for a month, and his empty promises toward noise regulation signified the end of my hope for a peaceful existence there. I’d given up completely on Hilda by then; on the few occasions when I was compelled to knock on her apartment, she stopped answering. The paint toward the bottom of her door flaked away when my knocks progressed to kicks, but she stayed the course and resisted a conversation with me. The door rattled in its frame, the mutt yipped itself into a frenzy, and I eventually stopped knocking.

Instead I huffed and I puffed and hatched a new plan.

To be Continued

The Ring

She’s known as “The Cat Lady.” Probably because of the cats rushing ahead of her for scraps. She waddles along, rolls of fat draping her body, ballooning her legs, blending her breasts and stomach, dripping down her right arm like candle wax. Her left arm, however, is withered, thin and twisted, as if the first dying branch of a waterless plant. She shuffles to the dumpster, runs her fingers through her downy white hair, pushes the glasses to her face and begins rummaging in it. Customers from the nearby restaurant, to which the dumpster belongs, will comment, joke about, or even sling insults at this hideous troll digging about in the trash. But there was a time when she was vibrant and happy.

She’s known as “The Cat Lady.” Probably because of the cats rushing ahead of her for scraps. She waddles along, rolls of fat draping her body, ballooning her legs, blending her breasts and stomach, dripping down her right arm like candle wax. Her left arm, however, is withered, thin and twisted, as if the first dying branch of a waterless plant. She shuffles to the dumpster, runs her fingers through her downy white hair, pushes the glasses to her face and begins rummaging in it. Customers from the nearby restaurant, to which the dumpster belongs, will comment, joke about, or even sling insults at this hideous troll digging about in the trash. But there was a time when she was vibrant and happy.

Howdy Neighbor

Bart Robbins’s reaction was a standard physiological response. His blood rushed from his extremities and pooled in his vital organs. His heart pounded. His head felt like an expanding balloon. His adrenal glands released an obscene amount of adrenalin. His thinking reverted to flashes of instinctual impulses. This physiological response is known in the science community as the “fight or flight” instinct. At that moment, Bart could have probably outrun a high school track star or maybe even have throttled a man to death with his bare hands.

Bart Robbins’s reaction was a standard physiological response. His blood rushed from his extremities and pooled in his vital organs. His heart pounded. His head felt like an expanding balloon. His adrenal glands released an obscene amount of adrenalin. His thinking reverted to flashes of instinctual impulses. This physiological response is known in the science community as the “fight or flight” instinct. At that moment, Bart could have probably outrun a high school track star or maybe even have throttled a man to death with his bare hands.

Bart Robbins wanted to do the latter.

The Umbrella

Harvey Paine sat at a beat up table in The Captain’s Quarters. He watched Fred stumble from the bathroom and stretch for the bar like a marathon runner for finish tape. “I’ll take anoder one,” Fred demanded, pulling a worn, crumpled dollar bill from his pocket and slapping it on the bar’s top. The television over the bar squawked about the recent assassination attempt on President Reagan. The newscaster’s voice saying, “Once again, President Reagan has been shot. Details are still coming in at this time, but we have reports that the president and two other men, one of which may be James Brady, have been gunned down by an unknown shooter.”

Harvey Paine sat at a beat up table in The Captain’s Quarters. He watched Fred stumble from the bathroom and stretch for the bar like a marathon runner for finish tape. “I’ll take anoder one,” Fred demanded, pulling a worn, crumpled dollar bill from his pocket and slapping it on the bar’s top. The television over the bar squawked about the recent assassination attempt on President Reagan. The newscaster’s voice saying, “Once again, President Reagan has been shot. Details are still coming in at this time, but we have reports that the president and two other men, one of which may be James Brady, have been gunned down by an unknown shooter.”

Fred gripped the edge of the bar, closing one eye to get a better look at the television screen. “Good,” he bellowed, “I wisssh they killed the muva Fuga. He’s a actor, not a prez-dent.”

The bartender of the Captain’s Quarters at that time was Gray Lewis. Gray was drying a clean glass with a dirty rag and he didn’t bother to look at the man gripping his bar. Gray said, “Take it easy, Fred.”

Fred, who had complained about four prior presidents while gripping the same bar, pointed at Gray, Fred closing one eye again to get a better view. He said “Look, you led me tell you something about Prezdent Reagan.” Of course, Fred could say all he wanted, Gray wouldn’t bother to hear it.

Charlene, the waitress at The Captain’s Quarters, appeared beside Harvey’s table. “That’s something about the President, huh?” she said.

Harvey flinched. He hadn’t noticed the woman was standing beside him. “What?”

“The President. Getting shot and all. It’s kind of crazy.”

“Oh, the president, yeah.” Harvey didn’t look at the waitress or the newscast on the television, or at Fred any longer, for that matter. He now stared at the untouched beer bottle across the table from him, the bottle a twin of the one in his own hand.

Charlene said, “You want me to put that on ice, hon?”

Harvey regarded the beer for a moment and said, “No, it’s fine, Charlene, its owner should be here any minute.” Harvey reached for a pack of cigarettes sitting in the center of the table, but when he noticed the bar’s front door open and shut, he stopped, pushing the cigarette pack back to the table’s center.

A younger, better-dressed, slighter version of Harvey stepped into the bar. The man scanned the room, his eyes fighting their sudden plunge into the dimness. When the man’s eyes adjusted, he spotted Harvey. The younger, better-dressed, slighter version of Harvey approached the table.

Harvey said to Charlene, “In fact, here he is now.”

Earworm: Part 1

Hope

Thursday, September 8, 1994

William Knight

Hope Ferretti sat in her homeroom, her head propped on her hand, propped on her elbow, propped on the desk, wondering why the name,

William Knight,

kept turning in her mind. It was as though she woke with the name nagging her, as if she’d fallen asleep with the radio on and the last song playing before she drifted off to slumber had yet to evacuate her brain. She lifted her head from her hand and said, “Who’s William Knight?”

“William Knight?” Tim Ford said. Tim sat beside Hope in homeroom—one of those people who had to answer a question before anyone else had a chance to. He said, “William Knight is the Indiana Hoosier’s basketball coach. He—”

“That’s Bobby Knight, you idiot,” Joel Fitch said from behind them. When Hope turned to look at him, Joel froze for a moment, her dark eyes locking onto his ice-blue eyes, then he grinned a smile of casual rebellion, although he was far from the rebel type. Joel Fitch was the school’s superstar, the heir apparent to Mystic Island High School’s sports legacy. Joel said to Hope, “I think William Knight’s a student here.” He turned to Tim, saying, “Wasn’t he that new kid in gym yesterday?” Tim shrugged. Joel said to Hope, “Why? What about him?”

“I don’t know, name’s just stuck in my head. It’s like when you can’t get a song out of your mind. You ever had that?”

“An earworm,” Tim said.

“A what?” Hope and Joel said simultaneously.

“An earworm. That’s what that’s called, when you have a song stuck in your head.”

“You don’t know the name of one of the most famous coaches in sports, but you know what it’s called when you have a song stuck in your head?” Joel said to Tim.

“Yeah, well, I’m not really into…” Tim paused. Hope thought she noticed Tim wince. Tim, along with every other wannabe, worshipped Joel, and Tim just almost admitted to not being into sports—a major faux pa in the social hierarchy of the high school male. “…College basketball,” Tim said. “I only like pro ball.”

Joel grinned, about to retort, but he shook his head and turned his attention back to Hope. “Well, whatever it’s called, it looks like you got one of these earbugs.”

“Worms,” Tim said, “Earworms.”

“Still doesn’t help me with who William Knight is,” Hope said. “But thanks for the effort.” She rose from her desk as the bell rang, and the students scattered for first period.

***

Hope sat in her first period math class. The students waited for Ms. Bradford, who had a knack for arriving perfectly synchronized with the late bell.

William Knight.

There was that name again, clicking in her mind like a person keying a ham radio’s handset. But why did the name nag her as if resurrected from some distant memory? As if something of obscure importance?

A few straggling students arrived, and when the bell rang, Ms. Bradford lumbered into the room. She was a short, wide relic with gray-streaked hair and bulging eyes that seemed capable of rotating independent of one another like the eyes of a chameleon. Students of an ancient alumni class had dubbed her the “Bradasaurus,” and like folklore, the name passed from generation to generation by older siblings saying, Oh, I see you got the Bradasaurus this year.The woman dropped a stack of books and papers on the desk with a thud, and, after regarding the class with her rotating eyes, plopped into her seat. The springs of the chair screaming for mercy. Then, seemingly keeping one eye on the class and one eye on the stack of papers, she fished out the attendance list. “Katie Adams,” she wheezed.

“Heee-re,” Katie sang in response.

“John Doherty,” Ms. Bradford said. She paused for the answer. None came. “John Doherty,” Ms. Bradford repeated with more bass resonating in her voice. One of her eyes glaring at John, who was busy mouthing something to his neighbor.

John’s neighbor cleared his throat, gesturing with his eyebrows toward the Bradasaurus. John turned with a stunned look on his face. “Yeah?”

“Are you here, John?”

“Uh…”

“Shouldn’t be a question you need to think about.”

“Yeah.”

“Good,” Ms. Bradford said, making an attempt at a smile. After a few more names, Ms. Bradford said, “Hope Ferretti.” Hope was about to answer when she noticed, scrawled on the wood surface of the desk in smudged pencil wisps, the words: Hope Feretey’s got great tits! “Hope Ferretti?” Ms. Bradford repeated.

“Um, yeah, I’m here.”

“Wonderful. I’m so proud that you all are mastering roll call. With a little more practice, I believe you will all have the knack of answering when your name is called.”

Hope shook her head as she erased the smudged sentiment regarding her tits. Gee, who could’ve written that? Only any of the testosterone overdosed males of the eleventh grade. Or she supposed it could have been Melody Belum—whose very public coming-out, when she snuck onto the school’s intercom and proclaimed, “I’m a proud lesbian,” brought raucous cheers from the student body—but Hope figured Melody would have at least spelled Ferretticorrectly. Hope had all but erased her name from the desktop when Ms. Bradford said, “William Knight.” Hope stopped erasing and looked at Ms. Bradford, as if confirming the woman had spoken.

The response came from over Hope’s shoulder. Someone saying, “Here.”

Hope’s head snapped back. In the back corner of the room, scrunched down like a crab trying to bury itself in sand, was the new kid. He was thin, but not sickly—the body of a boy yet to fill out—the thinness bringing out his high cheekbones and hooked nose. A thick nest of black hair fell over his forehead, almost covering his dark, almost black, eyes. Those dark eyes met her gaze for a moment. The kid flinched, looking as if wanting to bury himself a little more. And a strange, convulsive chill raced up Hope’s spine. It was a nondescript feeling of vague association, but association to what, she wasn’t quite sure.

***

Hope was exchanging one book for another in her locker when someone called, “Hope.” She turned and saw Joel running up to her. The late bell was approaching and a few, scattered students dug in cluttered lockers for books, lost pens, pencils, homework assignments crammed into dark corners. But Hope accepted that she would be late. She was always late third period. It was an unspoken rule, Mr. Levin’s class started five minutes later than advertised—a five-minute buffer where students leisurely wandered into the classroom. Mr. Levin liked being the nice guy too much to bag tardiness. As for Joel being late, he had Gym third period, and God help the gym teacher reprimanding the quarterback duringfootball season.

Hope handed Joel a book. “Hold this a minute,” she said as she foraged and reorganized. The late bell rang. Hope shut the locker. She took the book from Joel, pressing it to her chest, and regarded him with a smile that cut dimples into her cheeks. A few seconds of silence passed before she said, “Did you want something?”

“Me? No. Why?”

“Because you ran up to me calling my name.”

“Oh. I was just, you know, saying hi.” He switched his weight from one foot to another and ran his hand through his hair. “Hi,” he said.

“Hi.” She regarded him a moment longer. “Then, I guess I’ll talk to you later?” she said, turning to walk to class.

“You busy tomorrow night?”

Hope turned to face him. “Tomorrow night?” she said, feigning ignorance.

“Uh-huh.”

“Why?” she said, over-feigning ignorance.

“I was just wondering,” he said with a casual shrug. “Are you?”

“I don’t think so.” She leaned against the lockers, hugging her books to her chest.

“Oh, well, do you think, um, maybe you’d like to do something or something?” He glanced around the hall to make sure they were alone. “You know, with me?”

“Like a date?”

“No,” Joel said. Hope raised her eyebrows. Joel saying, “All right, yeah. I guess.”

“You guess? I’d like to be sure before we went.”

“Yes. I am asking you out on a date, all right?”

“Why didn’t you just say that in the first place? What are you, Danny Zuko?”

“Look, do you want to hang out Friday night or not? You know, maybe we could, like, do something or something—What’s so funny?”

Hope spoke between hitches of laughter, “You. You’re always so confident and sure of yourself, but you suck at asking a girl out. I’ve just never seen you so flustered.”

“It’s just weird. I mean, I’ve known you forever and always wanted to…I mean, we’ve been friends so long, but you were with Sean… Look, do you want to go out with me or not?”

“Well,” Hope rolled her eyes, letting the word hang in the air.

“Uhg.”

“Yes.”

“Really? Good. Now, that wasn’t so bad, was it?”

“Yeah. It kind of was.”

“Okay, fine, I gotta get going. I’ll see you later, in English” Joel said. He ran off to the end of the hall, waved back at Hope, and then cut down another hall. Hope watched him go, and when he was out of sight, she walked off to Mr. Levin’s class.

***

Hope sat at one of the cafeteria’s tables. The one in the middle. She wasn’t sure who’d originally chosen the center table—probably her friend Tara Larson, now sitting to her right—it’s as if they’d all been drawn to the spot. The center of the room. The center of the school. Hope, would have preferred to sit in one of the corners. The side tables where the outcasts sat. She glanced over at the table toward the back corner of the cafe. Her head caulked, her eyes narrowing a moment. “Who is that kid?” she said.

“What kid?” Tara said, looking up from her lunch and turning to scan the other tables. Tara was a petite girl with auburn hair that hung down her back in spiraling curls.

“The one at that table,” Hope answered, nodding toward William Knight. “See him? The one listening to George Banterman.”

Jennifer Waltson craned her neck to look as well. “Which one?” she said.

“That one, there,” Hope said. “See, he’s looking over here. His name’s William Knight or someth—”

Before Hope could finish, Tara turned toward her with the expression of one discovering something infested with maggots. “Oh, my God, that kid is so fucking creepy,” Tara said. She was capable of slipping the F-word into any conversation—her childlike expressions and tiny voice adding a shock-value to the word that would blush a rap star.

“You don’t know who that is?” Jennifer said, brandishing her knowledge with a self-satisfied flourish in her voice. Jennifer’s mother was the school’s secretary, a woman that lost all tact when speaking around her daughter, facilitating a running encyclopedia about every student in the school—and most of the staff, for that matter—a treasure-trove of gossip on anyone from the principal to the meekest of students. “That’s William Dey…” She paused a moment, just to allow the information to sink in for her tablemates. It didn’t sink in for them, so she added, “The Dey murders? Hello?”

“Really?” Hope gasped.

“You mean that guy that buried his wife’s head in the backyard?” Tara said.

“Yup,” Jennifer said with her air of self-importance.

“I thought the kid was sent away to live somewhere else with family. Why would he come back?” Tara said.

“His stepfather or adopted father or whatever tried to kill him. So they had nowhere to go but back here. They still owned the house. I mean, who would want to buy it?”

“Tried to kill him?” Tara huffed. “A family of fucking psychos, apparently.”

“That’s just what I’ve heard,” Jennifer said—she didn’t need to state her source.

“Why are you asking about him?” Tara asked Hope, peering over her shoulder again at William Knight. “He keep fucking staring at you or something?”

“No,” Hope said. “He’s in my math class. Just wondered who he was.”

***

Hope and Tara walked toward the cafeteria doors. Tara was yapping about how Mandy Bryant said that Donna Marrison called Julie Haggar a slut, just because she slept with half the basketball team, when she knew it was, like, Mandy who said it all along, and really, who is Mandy to—

A lurking form standing before them halted Tara’s story. Hope looked up, her eyes meeting the eyes of William Knight. He then said something so unexpected and random that it stuck with her, a bur in her mind for the rest of the day, into the night, and beyond. He said it so matter-of-factly that it sounded as if it were the revelation to a question she had all her life. He said, “I’mWilliam Knight.” And then he walked away.

Hope and Tara stared at the boy as he disappeared into the crowd.

“What the fuck was that all about?” Tara said.

Hope shrugged.

“Weird,” Tara said before picking up her story where she left off, as if never interrupted in the first place, “…start trouble between Donna and Julie when…”

But Tara’s words went unheard. Hopes thoughts focused only on the boy from her math class, and she couldn’t let go of the words he stopped to tell her. I’m William Knight.

Read more on Amazon Vella

The Skeleton: Part 1 — A Stringless Marionette

Vincent Stone crouched beside the car. He coughed twice, holding down his dinner, and closed his eyes. He was frozen, alone, scared, his heart pounding through his body. “Oh God,” he whispered. He wasn’t sure if he’d ever felt this way. Vincent Stone was always calm. Vincent Stone was always collected. But now, cool and calm Vincent Stone was crouched next to his car, about to puke up a $300 dinner and piss on his Armani shoes.

Vincent Stone crouched beside the car. He coughed twice, holding down his dinner, and closed his eyes. He was frozen, alone, scared, his heart pounding through his body. “Oh God,” he whispered. He wasn’t sure if he’d ever felt this way. Vincent Stone was always calm. Vincent Stone was always collected. But now, cool and calm Vincent Stone was crouched next to his car, about to puke up a $300 dinner and piss on his Armani shoes.

He stood up, rocking a little like a man who’d spent the night with Jack Daniels. But Vincent Stone was sober. And unfortunately, he was awake. This was no dream. He tried to take a step, his legs not responding. A marionette with no strings. C’mon. Left, then right, left, right…. He almost threw-up again, bending over, panting white puffs of breath. He took a deep gulp of cold air that bit at his lungs. That’s it. Slow, deep breaths.He shut his eyes, and his face slowly reassembled.

As he walked away from the car, the headlights stretched his shadow ahead of him in a long, dark path, and his senses and thoughts began to return. He stepped onto the old pier that jutted, suspended over the Ocean, and he leaned his forearms on the wooden rail, watching the black water. He liked the ocean. Even in the dark it was reliable. It would always be wet. Always taste salty. And even if it decided to show off by pounding the coast with a storm, one could trust it to be calm again. It was definite. It followed rules. Unlike life. Who’d have guessed that when he woke up this morning, he’d run into this kind of a problem?

His hand buried into the pocket of his long, black overcoat, happening upon his lighter and cigarettes. He pulled them out, hands shaking, following the usual routine of extracting a cigarette and igniting it with the gold lighter. He welcomed the smoke into his lungs and watched snowflakes descend and disappear into the ocean. He blew a stream of smoke into the air and turned to look at his Porsche, the engine purring. Snow fell in the headlights and collected on the dirt road. Occasionally, the intermittent wipers would sweep across the dark windshield, snuffing another generation of snowflakes that had gathered.

To Be Continued