The cover of the notebook was faded, drained of its color by time. Like the brick facade of some boarded-up firehouse, it could hardly be called red at all. More of a pink, really. The edge that opened to the pages within was tattered by its lengthy term in the bedside drawer, and the spiral, at one time a perfectly-aligned chrome coil, had lost its shape—the tiny loops bending into one another like a bench-load of old men. “Summertime Blues” ribboned across the middle of the cover, words placed there by a careful hand. The title set this notebook apart from the others in the drawer. About a half dozen of them were crunched in there behind a neglected Bible, a litter of foam ear plugs and a bound collection of sweepstakes entries. This evening, the other notebooks were still in his mom’s drawer back at the apartment. He only removed one at a time in order to avoid suspicion. With a little patience, there’d be plenty of time to eventually read them all.

The cover of the notebook was faded, drained of its color by time. Like the brick facade of some boarded-up firehouse, it could hardly be called red at all. More of a pink, really. The edge that opened to the pages within was tattered by its lengthy term in the bedside drawer, and the spiral, at one time a perfectly-aligned chrome coil, had lost its shape—the tiny loops bending into one another like a bench-load of old men. “Summertime Blues” ribboned across the middle of the cover, words placed there by a careful hand. The title set this notebook apart from the others in the drawer. About a half dozen of them were crunched in there behind a neglected Bible, a litter of foam ear plugs and a bound collection of sweepstakes entries. This evening, the other notebooks were still in his mom’s drawer back at the apartment. He only removed one at a time in order to avoid suspicion. With a little patience, there’d be plenty of time to eventually read them all.

Cooper squatted on the wobbly sheet of plywood high in the tree. Dusk would settle soon, and he imagined he would end up descending in the dark. A bird cawed, and he watched it dart from one treetop to another, he then returned his attention to the notebook. Its spiral binding snagged his shirt. He wove it back out of the material, leaned against the tree, and flipped open the cover. Above him, tassels of willow danced in gentle loops from the top branches, pixilated by the fading glow of sunset. They were like tiny spires, he thought, each blending in with the others like an accusatory threat. There were hundreds of them, and if they were to fall from branches like tears, he’d be buried in their thrust—invisible to the rest of the world. Just like his mother. He didn’t want to duck beneath the wing of anonymity as she’d done, and he toyed with the idea of abandoning his platform and climbing the tree’s pinnacle to avoid his far-fetched burial fantasy. Instead, he settled into the first pages of the notebook.

July 5, 1980

The 4th started off as an amazing day, but I should’ve seen it coming—the disappointment that would be thrown on me later. He does it to me every time—builds everything up like we’re the most durable couple in the entire world with nothing but plump babies and picket fences in our future. But it never takes long for his tune to change. I really don’t know what’s going to happen here, and I’m a little scared. I thought things might change yesterday. Grandma used to tell me “your mind is like a tire on the car: it can always be changed.” But it doesn’t seem like that adage applies to Hank.

I should’ve known things would go a bit haywire when I saw him show up with a cooler of beer. He knows I can’t drink because of my “condition”. He’s so into denying that this situation even exists that he tells me I can drink until I’m showing. That’s just another lie that he’s told himself so many times that he might actually believe it by now. He had three empties rattling around on the floor of the car by the time we got to Black Rock Beach. He said we needed to be there by noon to secure a spot for the fireworks at dusk, but I think what he really wanted was a place to put away a 12 pack while looking out at the bikini girls (who aren’t pregnant) and think about the possibilities. “Baby this” and “baby that” he keeps saying. He sweetens up all of his lame excuses with the glass-bottomed hope that I’ll see things his way. But I wish that he would just see things my way and I used yesterday as an opportunity to tell him so.

We had just gotten to the beach, and as I’d predicted, we were some of the first people there. The tide was creeping in gently, and after we spread out the blanket, I sat under the umbrella while he set up his cooler and radio. I watched for a while as the barge off shore was loaded up with fireworks. I wonder how you get a job being one of those people, floating out on top of the ocean with a boat-full of explosives!

Toward the end of the first six pack he nodded off, and I sat there and watched some of the other people who’d started setting up their stations on the beach. It’s strange; since the doc told me I was pregnant I’ve lost interest in reading books. I guess it takes something as real as this to make me disinterested in the world of fiction. One cool thing about it is that I am more inspired by people-watching now. It’s so fun to sit and check them out, just imagining what is hidden in the deep folds of their lives. I wonder how many of them have parallels with me. A fat old lady sitting in a lounge chair, a lifeguard walking up the beach with a newspaper tucked under his arm, a little girl digging frantically in the muddy sand where the tide rolled in. I wondered about where they all lived and what they were each thinking. I rooted for the little girl’s sand-creation to survive the tide.

When Hank woke up, his back was streaked red in the spots he hadn’t been able to reach with the sunscreen. I almost laughed but I didn’t want to risk pissing him off or sending him into one of his “poor me” fits of silence. He can be such a baby sometimes! I needed to keep him in good spirits so I played the motherly role (hoping he’d take notice of my ability in that area) and soothed his back, rubbing in extra lotion. Finally, he rolled over and reached into the cooler for another beer. He was all groggy and when he yawned I could see sticky lines of saliva connecting his lower and upper lip. Such a lovely sight; the father of my future child! I figured it might be a good time to discuss the baby, but when I brought it up, he raised the palm of his hand toward my face to shut me off. He doesn’t want to talk about it!

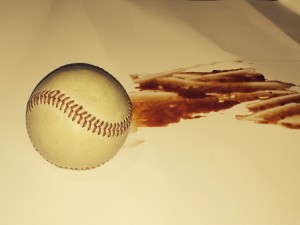

Hank needs to take some responsibility for our child. The only time he mentions it is when he tells me I should just get rid of it. “We’re not ready for it right now,” he says. I know that he’ll never be ready for any responsibility. So I just sat there and watched him pour another few beers down his throat. When dusk finally happened, the fireworks went off as planned; big blossoms of light radiating out above the people gathered on the beach, spiraling toward the water, but disappearing before they made it to the surface. It’s amazing how there is such a beautiful bloom, and then the next moment there is no evidence that it even existed.

I feel like our relationship is similar; we had our fireworks and now when I try to remind him about our responsibility, he doesn’t want to talk about it. He’d rather pretend that the fireworks never happened.

I’m scared . . . .

Cooper shut the journal and slid it into his back pack where he was sure not to forget it. Anything left behind was a potential victim to rain or wind or theft. And she’d just about kill him if she found out that he’d been prying into her private thoughts. He sat there—up where he always hung out during the intermissions between school and sunset. It was a place apart from his mother’s nagging questions and away from any sense of accountability. There was no chance of encountering the heady stare of his English teacher, Miss Foster, or the mocking catcalls of the jocks who rode the school bus with him. Up there in the tree he needed to look out for Number One and that’s all. A liberating idea. He was free to read from his mystery stories—Agatha Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Allan Poe—uninterrupted, or mimic the movements of squirrels (as he often did) in an attempt to study their habits. During the past week, he began to swipe the journals from his mother’s nightstand. Real mysteries were buried in those pages, and he knew that he might begin to understand her life if he took the time to figure them out.

He always tried to avoid making personal connections with the entries, maintaining the “outsider-perspective” of a fiction reader. It was a devise that was suggested to him by one of his elementary teachers a few years back, and he never gave it much thought back then while reading James and the Giant Peach or Bearstone. But his mom’s journal entries were different, almost inviting him to guess where he fit into the happenings. Often he was mentioned by name as she wrote a mixed bag of entries describing times he made her proud—like when he designed the runner up car in the pine box derby back in Cub Scouts—but also throwing in her ideas about things he did that pissed her off. He read her impressions from the day he scribbled with crayons on the bathroom wall when he was five or six years old—she was thinking of completely shutting him off from any Christmas presents that year.

The entry he just finished was in a class of its own. It painted an image of his mother in her fragile youth. In her own words, she appeared confused and scared, but perhaps more important was the inner struggle that tortured her. As long as he’d known her, his mom had never been a huge advocate of giving voice to her opinions unless it regarded him. He could tell when something didn’t sit well with her, but she usually let it slide and opted for silence instead. And that seemed to be the case with the journal entry. But this was different. He was implied in there—an unborn child with a hurting mother and a calloused father. Hank. There was a name he’d never heard uttered in their apartment. Was Hank indeed his father? The prospect of asking her about Hank bore visions of an explosive battle. Not only would he be implicated in stealing her privacy, but the question would act as a tool, violently tearing the stitches from a wound that certainly would never heal. He understood that she must carry deep resent for this man, Hank, and asking about their relationship would do nothing to lift the burden.

Until he knew more.

Through the thick foliage, the sharp report of a backfiring car was followed by squealing tires. He imagined a jacked up Camaro peeling across the parking lot of their apartment complex, thudding over the speed bumps and fishtailing out into the road that connected the development with the rest of the island. It happened all the time. He had fantasized securing a steel cable across the access road, anchoring one end to the sign that boasted “Black Rock Villas” in gawky, gold lettering, and the other to a light pole. It would bring great satisfaction to watch the car halted by a shower of sparks from the capsized light post or else drag away the sign that marked the driver for the world to see. It wasn’t exactly a status symbol to claim residency at “The Villas.” It was the stigma of living there that had spurred Cooper into sneaking glances at his mom’s journal.

At first, he’d wanted to learn enough about her life to know how they’d landed in the housing complex—a single mother and her only son. He waited for her to get into the shower before going to her bedroom to read the journals. Most were filled with trivial entries, describing new recipes she saw on TV or an info-mercial that captured her interest. After a few days, though, he discovered a hard-bound notebook toward the bottom of the night stand drawer. A light stain—coffee or coke, he guessed—smeared its cover like some amorphous silhouette. In it, he read about her arguments with his grandfather and about people named Marjorie, Hank, and Leonora. Although he remembered his grandpa, he never met or even heard of the rest of them. But the descriptions of every day events in his mom’s life carried a thrill that he couldn’t explain. And when he almost got caught prying into the journal that afternoon, he disciplined himself that only in his private place could he read the entries.

The tree fort was a secret that he believed was safe from the rest of the world. Countless afternoons of scouring the areas around the apartment complex trash dumpsters had yielded the raw materials to make it all happen. The rectangle of plywood that turned out to be the floor was the first item discovered, and the first installed. Tiny fragments of carpet clung to the rusty staples that lined its rough surface and he’d spent an entire Saturday sanding it smooth and then lugging it out to the woods, keeping a careful eye over his shoulder to make sure that nobody was tracking his movement. His mom had a coffee tin full of odd shaped nails and screws and he borrowed a few of them to affix the platform in the crook of a large willow tree he scoped out during the previous spring. He noticed the perfect curvature while out collecting soil for a school science project and he immediately earmarked the spot for his “getaway.”

During elementary school, Cooper had friends whose fathers built them tree houses to go along with their jungle gyms and sand boxes and rope swings. But, while those contraptions proved fun for most kids his age, it didn’t seem natural for him to use them. It was like using a public restroom—not as relaxing as home. So, the idea was planted for many years and it felt good to finally set out to make good on the concept.

A shelving unit had been tossed, along with some wrought iron handrails, and on a Sunday in May, he rigged up a rope to hoist all of the materials up into his secret nook. As dusk neared on that evening Cooper experienced a sense of accomplishment like no other in his life. He leaned out over the wrought iron railing and sucked on a cigarette, his day’s work complete. When darkness descended on the woods, he leaned back and scattered a flashlight beam across the old rack of shelves. Remnants from torn-away stickers lingered on their wooden surface, and he made a mental file of all of the things he planned to bring up there to transform it into his home away from home. It was like a satellite bedroom and it pleased him deeply to think about the prospect of hanging out there without the possibility of his mother’s voice needling through the door. “Could you take out the trash?” “Can you run to the store for me? I’m out of cigarettes!” “Did you do your homework?” Nothing to listen to but the song of birds and whisper of leaves as the wind riffled through them.

He looked to the spot and was pleased to realize that it had turned out pretty much as planned. A small stack of books was wedged into the lower shelf, while the upper shelf trophied a pair of candles. His mom always warned him against burning candles in the apartment, telling him stories of neighborhood kids setting the house on fire during her childhood. She described the entire sky lighting up in a deep orange tint as if the night time was melting. “It was just like a fireworks display,” she told him, and he could still remember wondering whether she’d ever seen an actual fireworks display that she could compare it to.

Now, as he zipped her journal into his back pack and prepared to head back to the apartment, he knew that she had.

To Be Continued